This article describes the secrecy and censorship that affected New Mexico during the original development of the Atomic Bomb. It was published the same day (August 6, 1945) that President Truman revealed the Atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima and that it had been developed in New Mexico.

| Document Type: | Newspaper Article |

| Historical Event: | New Mexico Role in WW II (1941-45) |

| Sub Event: | Manhattan Project |

| Origin: | Santa Fe New Mexican |

| Date: | August 6, 1945 |

| Author: | William McNulty |

| Permission: | Fair Use |

| Contributor: | Dan Jones |

Digital Text:

The Santa Fe New Mexican

August 6,1945

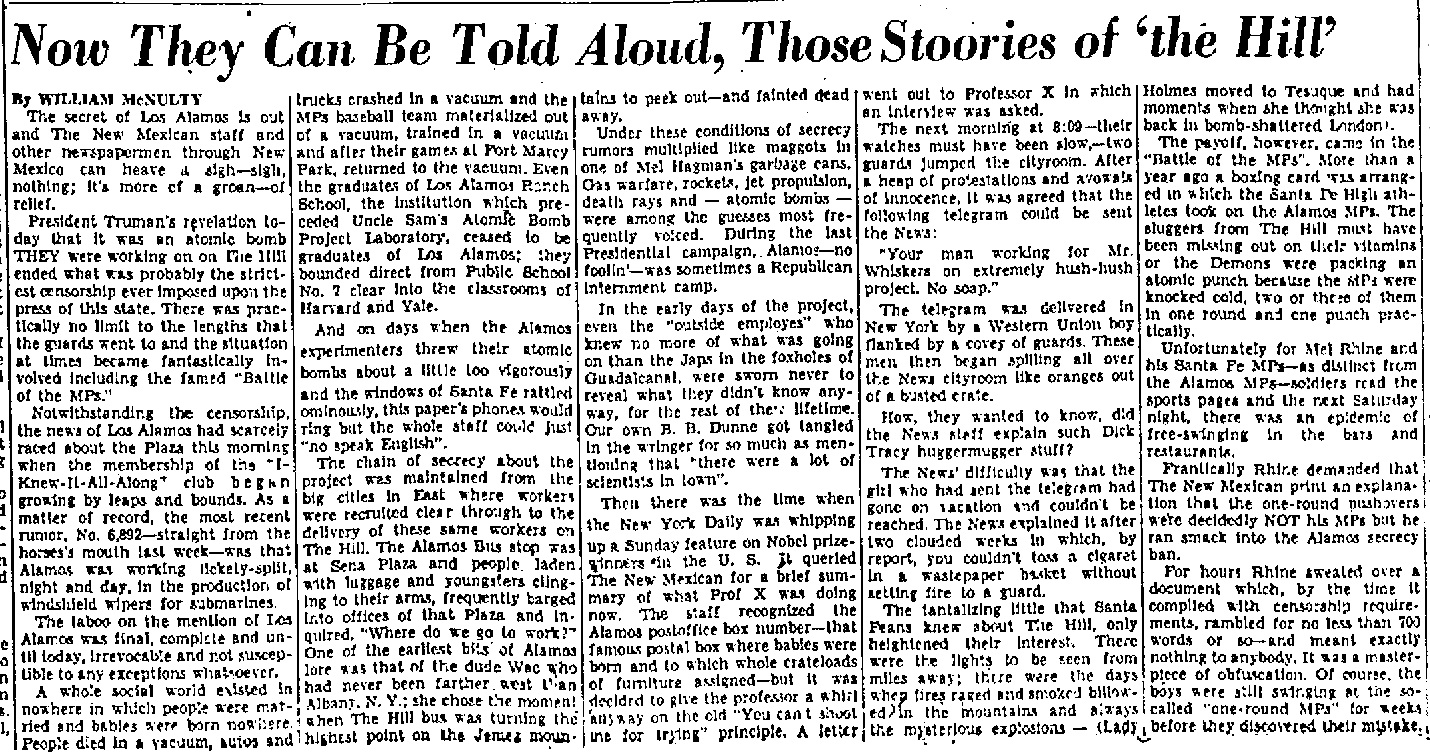

Now They Can Be Told Aloud, Those Stoories of 'The Hill'

By WILLIAM McNULTY

The secret of Las Alamos is out and The New Mexican staff and other newspapermen through New Mexico can heave a sigh—sigh, nothing; It's more of a groan-of relief.

President Truman's revelation today that It was an atomic bomb THEY were working on The Hill ended what was probably the strictest censorship ever imposed upon the press of this state. There was practically no limit to the lengths that the guards went to and the situation at limes became fantastically involved including the famed "Battle of the MPs."

Notwithstanding the censorship, the news of Los Alamos had scarcely raced about the Plaza this morning when the membership of the I-Knew-It-All-Along club began growing by leaps and bounds. As a matter of record, the most recent rumor. No. 6,892—straight from the horses's mouth last week—was that Alamos was working lickety-split, night and day. In the production of windshield wipers for submarines.

The taboo on the mention of Los Alamos was final, complete and until today, irrevocable and not susceptible to any exceptions whatsoever.

A whole social world existed in nowhere in which people were married and babies were born nowhere. People died In a vacuum, autos and trucks crashed In a vacuum and the MPs baseball team materialized out of a vacuum, trained in a vacuum and after their games at Fort Marcy Park, returned to the vacuum. Even the graduates of Los Alamos Ranch School, the institution which preceded Uncle Sam's Atomic Bomb Project Laboratory, ceased to be graduates of Los Alamos: They bounded direct from Public School No. 7 clear into the classrooms of Harvard and Yale.

And on days when the Alamos experimenters threw their atomic bombs about a little too vigorously and the windows of Santa Fe rattled ominously, this paper's phones would ring but the whole staff could just "no speak English".

The chain of secrecy about the project was maintained from the big cities in East where workers were recruited clear through to the delivery of these same workers on The Hill. The Alamos Bus stop was at Sena Plaza and people laden with luggage and youngsters clinging to their arms, frequently barged into offices of that Plaza and inquired, "Where do we go to work?" One of the earliest bits of Alamos lore was that of the Wac who had never been farther west than Albany, N. Y.; she chose the moment when The Hill bus was turning the highest point on the Jemez mountains to peek out - and fainted dead away.

Under then conditions of secrecy rumors multiplied like maggots in one of Mel Hagman's garbage cans. Gas warfare, rockets, jet propulsion, death rays and — atomic bombs — were among the guesses most frequently voiced. During the last Presidential campaign, Alamos - no foolin' - was sometimes a Republican internment camp.

In the early days of the project, even the "outside employees" who knew no more of what was going on than the Japs in the foxholes of Guadalcanal, were sworn never to reveal what they didn't know anyway, for the rest of their lifetime. Our own B. B. Dunne got tangled in the wringer for so much as mentioning that "there were a lot of scientists In town".

Then there was the time when the New York Daily was whipping up a Sunday feature on Nobel prize winners in the U. S. It queried The New Mexican for a brief summary of what Prof X was doing now. The staff recognized the Alamos post office box number - that famous postal box where babies were born and to which whole crate loads of furniture assigned - but it was decided to give the professor a whirl anyway on the old "You can t shoot me for trying" principle. A letter went out to Professor X in which an interview was asked.

The next morning at 8:09 - their watches must have been slow, - two guards jumped the cityroom. After a heap of protestations and avowals of innocence, it was agreed that the following telegram could be sent the News:

"Your man working for Mr. Whiskers on extremely hush-hush project. No soap."

The telegram was delivered in New York by a Western Union boy flanked by a covey of guards. These men then began spilling all over the News cityroom like oranges out of a busted crate.

How, they wanted to know, did the News staff explain such Dick Tracy huggermugger stuff?

The News' difficulty was that the girl who had sent the telegram had gone on vacation and couldn't be reached. The News explained it after two clouded weeks in which, by report, you couldn't toss a cigarette In a wastepaper basket without setting fire to a guard.

The tantalizing little that Santa Feans knew about The Hill, only heightened their Interest. There were the lights to be seen from miles away; there were the days when fires raged and smoke billowed in the mountains and always the mysterious explosions - (Lady Holmes moved to Tesuque and had moments when she thought she was back in bomb-shattered London).

The payoff, however, came in the "Battle of the MPs". More than a year ago a boxing card was arranged in which the Santa Fe High athletes took on the Alamos MPs. The sluggers from The Hill must have been missing out on their vitamins or the Demons were packing an atomic punch because the MPs were knocked cold, two or three of them in one round and one punch practically.

Unfortunately for Mel Rhine and his Santa Fe MPs - as distinct from the Alamos MPs - soldiers read the sports pages and the next Saturday night, there was an epidemic of free-swinging in the bars and restaurants.

Frantically Rhine demanded that The New Mexican print an explanation that the one-round pushovers we're decidedly NOT his MPs but he ran smack into the Alamos secrecy ban.

For hours Rhine sweated over a document which, by the time It complied with censorship requirements, rambled for no less than 700 words or so—and meant exactly nothing to anybody. It was a masterpiece of obfuscation. Of course, the boys were still swinging at the so-called "one round MPs" for weeks before they discovered their mistake.

Related Documents

- Notebook of Manhattan Project Testing

- Fuller Lodge - Los Alamos, NM

- FDR's Response to Einstein Letter

- Albert Einstein Letter to FDR

- Letter, FDR to Oppenheimer

- July 16, 1945 - First Atomic Bomb Detonation

- Trinity Site - Map

- Trinity Site - Survey Photo

- Trinity Site - Camera Bunker

- Trinity Site - Explosion

- Deadliest Weapons in World's History, Made In Santa Fe Vicinity

An educational resource for New Mexico high school history programs.